The Liberal Arts: Historical Roles and its impacts on Democratic Nations

“Indocti caelum rapiunt; Quisquis bonus verusque Christianus est, Domini suie est intelligat, ubicumque invenerit veritatem : It is the ignorant who snatched the kingdom of heaven; Let every good and true Christian know that truth is the truth of his Lord and Master, wherever it is found.”

Grammar

Logic

Rhetoric

Arithmatic

Geometry

Music

Astronomy

Grammar Logic Rhetoric Arithmatic Geometry Music Astronomy

What are the seven liberal arts?

“In our modern age, education has lost its soul. Students memorize facts without understanding. They use technology without wisdom. But the liberal arts offer something different. They restore the unity of knowledge, train the mind to seek truth, and prepare the soul for contemplation. [1]”

Around 500 to 400 years ago before common era (before christ), prior to any concept of formal/standard education exist in the western communities, the classical greek society developed a program to set free every person from the bindings of cultures, worldviews, the overall ways of life around them, and developed lasting and useful cultures/ways of life for seeking truth and development. The concept of the program was called ‘Paideia,’ translated here as a controlled transformation of a citizen—training of body, mind, and character to become whole and to analyze phenomena around them as a whole.

This Paideia pedagogy underpinned classical Greek civic life and later Western humanistic education. With Paideia as a guiding movement, further developments and institutionalization of ideas gave birth to the liberal education. ‘Liberal Education’ was an approach and set of curricular practices that emphasize broad knowledge across disciplines, critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and civic capacity rather than narrow vocational training, and it is specifically aimed to form free, reflective citizens that able to reason across contexts.

The early scholars, philosophers, and church figures then improved, popularized, and institutionalized the seven liberal arts from the Liberal arts. The timeline of the developments and the notable figures involved in the development of Liberal Education can be seen in the figure below

Trivium: Grammar, Rhetoric, and Logic

The early scholars formulated the Trivium (‘three ways’ in latin) to create a practical, staged curriculum that taught how to use language (grammar), how to reason about statements (logic), and how to persuade (rhetoric), providing the essential intellectual tools needed to read, interpret, and transmit classical and Christian learning across schools and monasteries in late antiquity and the Middle Ages [5]. The core historical drivers of Trivium are Recovery and transmission of classical learning: Educators needed a compact, teachable framework to pass on Greek and Roman texts; the Trivium packaged the verbal arts required to access those works [7], Practical pedagogy for early learners: The three arts were conceived as foundational skills—memorization and mastery of language (grammar) first, then analysis (logic), then expression (rhetoric)—matching how teachers organized instruction [8], and Institutional needs of the Church and monastic schools. Christian educators adopted and adapted classical curricula so clergy and scribes could read scripture, compose sermons, and argue theological points; the Trivium served those ecclesiastical functions [7].

Grammar:

Grammar in the Trivium is the foundational art that teaches the mechanics and rules of language so learners can read, speak, and write correctly; it is the first stage of the classical three‑part curriculum (grammar, logic, rhetoric) and prepares students for reasoning and persuasive expression in later stages, a model still referenced in modern classical education [5].

Logic:

Logic in the Trivium is the art of correct thinking and argumentation that occupies the second, formative stage between grammar and rhetoric; it teaches learners how to identify valid inferences, detect fallacies, analyze propositions, and organize premises into coherent syllogisms so that statements can be tested for truth and consistency rather than merely recited, and it therefore functions as the intellectual discipline that converts linguistic competence (knowledge of words, forms, and structures) into discursive competence (the ability to reason about claims and relations).[5]

Rhetoric:

Rhetoric in the Trivium is the culminating art of effective communication and persuasion, taught after students have mastered the forms of language (grammar) and the principles of correct reasoning (logic). It encompasses the processes of invention (finding persuasive material), arrangement (organizing ideas for impact), style (choosing words, figures, and sentence patterns), memory (techniques for recall), and delivery (voice, gesture, and presentation), all aimed at shaping thought and moving audiences. [5].

Quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy

The quadrivium (‘four ways’ in latin) is the medieval second stage of the seven liberal arts, which are arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Quadrivium is formulated as a mathematical curriculum after the Trivium to train students in quantitative and cosmic principles; its consolidation is commonly attributed to late‑antique authors such as Boethius and to medieval curricular practice that paired it with the Trivium to prepare students for higher philosophy and theology.

Arithmetic (The Art of Pure Number)

Arithmetic is the study of number itself. It deals with the properties and relationships of numbers, as understood without reference to space or time. For the ancients, numbers were not just tools but reflections of eternal truths. The Church Fathers, especially St. Augustine, saw in numbers the fingerprints of the Creator. In De Musica, Augustine writes about how numbers reflect God’s order and harmony in the universe.Arithmetic prepared students to understand the deeper mysteries of creation, where all things reflect divine measure and proportion. [1]

Geometry: The Art of Number in Space

Geometry studies numbers in space. It deals with shapes, sizes, and the relationships between physical forms. The ancient Greeks, especially Euclid, established Geometry as a logical science through his Elements, a work studied for over 2,000 years. St. Thomas Aquinas teaches that man’s mind is ordered to perceive truth through the order found in the world. Geometry helps to uncover that order. It also serves as a preparation for understanding the structure of sacred architecture, like the proportions of cathedrals. Therefore, Geometry is not just for engineers—it is a moral and spiritual training in order and clarity. [1]

Music: The Art of Number in Time

Music is the study of numerical relationships in sound. In ancient education, it was not simply entertainment. Music trained the soul in harmony, rhythm, and proportion. As Pythagoras discovered, musical harmony corresponds to mathematical ratios. The Church has always recognized the spiritual power of Music. Sacred chant, like Gregorian chant, is deeply mathematical and reflects the order of heaven. As St. Augustine said, “I am moved by the sweetness of sound, not for its own sake, but as it leads me to truth” (Confessions, Book X). Because Music joins the rational and the emotional, it was seen as a bridge between the mind and the heart. [1]

Astronomy: The Art of Number in Motion

Astronomy is the study of the heavens. It considers numbers in motion—especially the movement of the stars and planets. For the ancients, Astronomy revealed the glory of God. As Psalm 19 says, “The heavens declare the glory of God; the sky proclaims its builder’s craft.” Ptolemy’s Almagest and Aristotle’s On the Heavens laid the foundation for classical Astronomy. Medieval scholars like St. Albert the Great studied these works with reverence, seeking to understand God’s design in the cosmos. Besides its scientific use, Astronomy was spiritual. The order of the heavens was seen as a reflection of the moral order on earth. To study the stars was to contemplate the mind of the Creator. (Check Reasons To Believe by Dr. Hugh Ross, who studied stars to reason better interpret God’s revelation in the Holy Bible)[1]

Institutionalization of the seven liberal arts

In Roman and late‑antique education, the liberal arts were practical, status‑oriented training: young elites learned grammar and rhetoric to read classical texts, compose speeches, and perform in public life, while mathematical studies prepared them for surveying, calendrics, and technical tasks. Classical rhetoricians and educators (e.g., Isocrates and later Roman grammarians) emphasized mastery of language and oratory as civic skills; these practices were absorbed into schoolroom routines of memorization, textual analysis, and declamation.[7]

Late‑antique authors such as Martianus Capella and Boethius helped codify the seven arts by grouping the verbal arts (the Trivium: grammar, logic, rhetoric) and the mathematical arts (the Quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy), creating a compact curriculum that could be taught in monastic and cathedral schools. This codification made the arts portable across institutions and languages, which was crucial for preserving classical learning through the early Middle Ages.[1]

The seven liberal arts began as practical training for Roman elites—teaching language, argument, and number for public life—and were later codified (Trivium + Quadrivium) by late‑antique and medieval educators to form the foundation of university study; over centuries their emphasis on literacy, critical thinking, and quantitative skills shaped the idea of a broad foundational curriculum that underlies many modern general‑education programs. Prominent examples include Columbia University’s Core Curriculum, the University of Pennsylvania’s General Education, Texas State’s Core Curriculum, and many state‑university and liberal‑arts college core programs used across the U.S., including at the University of Mississippi.

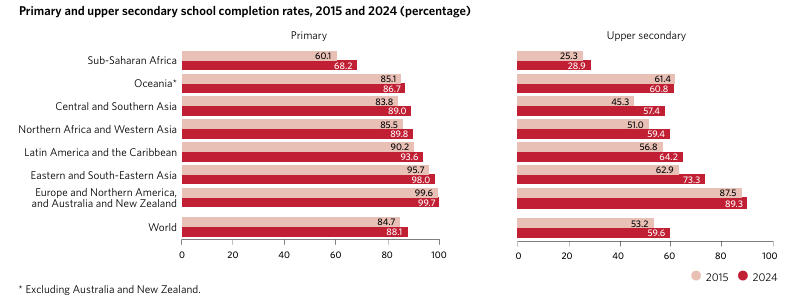

Completing primary and upper‑secondary education matters for democracy because schools are where citizens first acquire civic knowledge, participatory habits, and the cognitive skills needed to evaluate claims and engage with public life: students exposed to sustained civics instruction and active learning (debate, service learning, mock elections) are more likely to register, vote, volunteer, and deliberate as adults, while higher overall completion correlates with greater turnout and more informed voting behavior [10] (Check the figure above to see the most recent statistical data from the 2025 United Nations Report on primary and upper secondary completion rates based on world regions). Education builds critical reasoning and media‑literacy skills that reduce susceptibility to misinformation and improve the quality of local deliberation—so communities with higher completion rates tend to have more constructive public meetings, better school‑board debates, and more effective civic organizations [11]. Schools also create social networks and civic infrastructure—peer groups, alumni ties, and extracurricular organizations—that mobilize voters and sustain volunteerism; these networks amplify information flow and lower the transaction costs of collective action, which strengthens neighborhood problem‑solving and local governance. Economically, higher completion expands the skilled workforce available to local institutions (schools, courts, municipal offices), improving service delivery and institutional legitimacy, which in turn reinforces citizens’ trust and willingness to participate. However, the democratic benefits depend on equity and curriculum quality: if completion gains are concentrated among advantaged groups, political influence becomes skewed and representation suffers; likewise, diplomas without substantive civic learning produce weaker effects, so policymakers should pair access initiatives with robust, experiential civic education [12]. Practically, communities should pursue two linked strategies—raise universal access to upper‑secondary pathways (remediation, flexible scheduling, financial supports) and embed active civic learning across grades—because the combination increases both the quantity and the democratic quality of graduates. Finally, monitoring disparities by neighborhood, race, and socioeconomic status is essential: equalizing completion narrows civic inequality and prevents the political marginalization that erodes democratic responsiveness, whereas neglecting equity risks amplifying polarization and weakening local collective capacity [13].

Citations:

[1] W. C. Michael, “Classical Liberal Arts Academy,” Classical Liberal Arts Academy, Dec. 11, 2025. https://classicalliberalarts.com/blog/seven-liberal-arts/ (accessed Jan. 28, 2026).

[2] A. F. West, The Seven Liberal Arts: Alcuin and the Rise of the Christian, 2010.

[3] United Nations, “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025,” 2025. Available: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2025.pdf

[4] P. P. Duff, “Teaching and Learning English Grammar: Research Findings and Future Directions - 2015 - Front matter and Table of Contents,” Academia.edu, Dec. 08, 2014. https://www.academia.edu/9682760/Teaching_and_Learning_English_Grammar_Research_Findings_and_Future_Directions_2015_Front_matter_and_Table_of_Contents?utm_source=copilot.com (accessed Jan. 31, 2026).

[5] Copilot, "Grammar in the Trivium; Rhetoric in the Trivium; Logic in the Trivium" online assistant reply to Papua Center America, Jan. 31, 2026.

[6] The Holy Bible, King James Version, 1611.

[7] “Trivium,” Wikipedia, Jun. 01, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trivium.

[8] “Trivium & Quadrivium,” The Book of Threes, Mar. 06, 2005. https://www.bookofthrees.com/trivium/

[9] “What Are The 7 Liberal Arts? The Traditional Arts Revealed!,” Liberal Arts, Dec. 03, 2021. https://liberalartsedu.org/faq/what-are-the-7-liberal-arts (accessed Feb. 01, 2026).

[10] A. J. Perrin and A. Gillis, “How College Makes Citizens: Higher Education Experiences and Political Engagement,” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, vol. 5, p. 237802311985970, Jan. 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119859708.

[11] C. D. Kam and C. L. Palmer, “Reconsidering the Effects of Education on Political Participation,” The Journal of Politics, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 612–631, Jul. 2008.

[12] J. Chittum, K. Enke, and A. Finley, “The Effects of Community-Based and Civic Engagement in Higher Education WHAT WE KNOW AN D Q U E STION S THAT R E MAIN,” 2022. Available: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED625877.pdf

[13] A. V. Jensen, “Educating for Democracy? Going to College Increases Political Participation,” British Journal of Political Science, vol. 55, Jan. 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123424000486.